Jussi Koitela

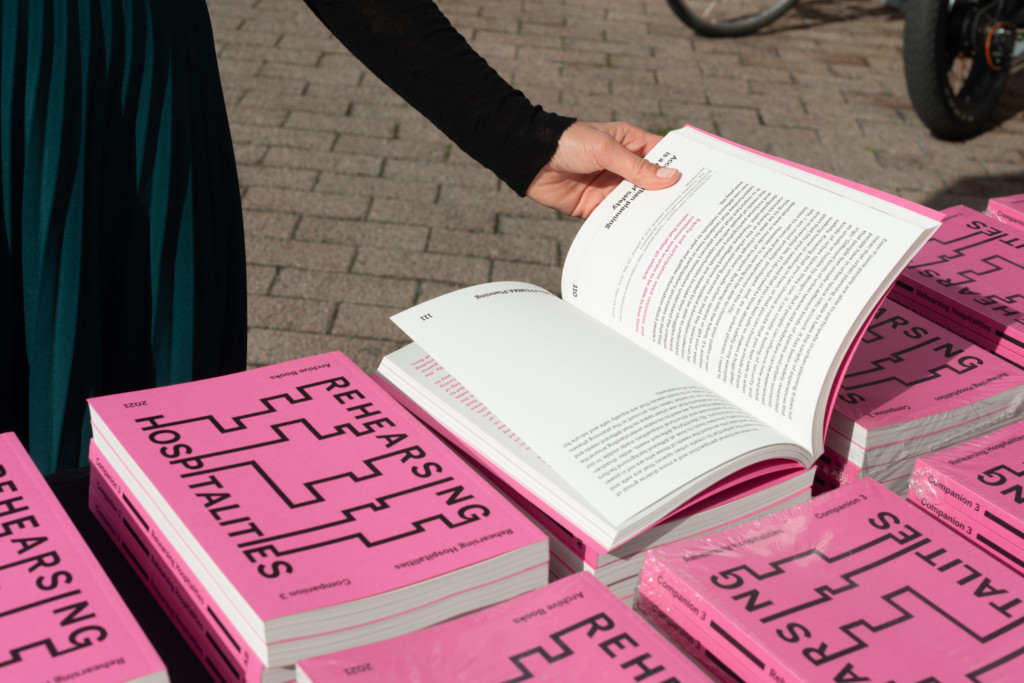

[The following text is an excerpt from Rehearsing Hospitalities Companion 3 which can be downloaded here.]

From the beginning of the Rehearsing Hospitalities programme in 2019 we – the programme curators – have been attempting to dwell (through reflecting, writing, thinking, gathering) on the challenges and shortcomings of the programme itself and art institutions in general. Throughout this time, it has become obvious that a multitude of problems and vulnerabilities are connected. We have learned that it is hard to work on specific, isolated questions concerning, for example, agency, equity, access and different ways of knowing and experiencing without acknowledging their interconnectivity.

Upon what kind of power structures of knowledge and knowing are contemporary art and artistic institutions dependent? What are the ways that intersectional subjectivities open up new epistemic processes within the artistic field? How might dominant and institutionalized knowledges and forms of access be challenged from a range of perspectives? How can diverse access to language, environment, culture and archives produce more equal and just contemporary societies?

These are amongst the questions we have been asking throughout Rehearsing Hospitalities. In order to further address these pressing questions, and after thinking about how to be more hospitable towards different ways of knowing and accessing institutions or cultural and artistic production in a broad sense, it has become critical to think about:

For whom is it actually safe to be in these spaces of presenting, producing and experiencing art? How do practices and power structures connected to security and safety affect how different people produce and experience art? How can art be produced and experienced safely? How might we gather around art with others in safe and secure ways?

These issues are complex and it is hard to come up with a single specific starting point for working with them, especially when art institutions tend to understand safety and security as operating independently of each other. It seems that when art institutions and museums rooted in Western culture speak about security they are often referring to infrastructures and art objects, and security is largely targeted towards the physical aspects of the institutions. It is about safeguarding the property of the museum in the best interest of the public or owner of the objects. This is done, for example, by keeping the spaces guarded and through establishing protocols which dictate who can use the spaces and how.

On the other hand, safety, for example, might be present in the form of safer space guidelines, a tool intended to ensure the safety of museum visitors and event participants. These safety measures are something museums offer to their visitors within the parameters of the institutions’ support structures. To extend these safety structures outside of institutions’ spatial infrastructures or the museum’s core demographic – generally middle-class communities that normally visit the institution or engage in its activities – seems to be a much harder job to do.

Many questions arise:

What is the aim of this division between security and safety? What and who’s security or safety is privileged over others? Who is responsible for each of these ‘targets’ of security and safety within the institution? For who and what kind of objects and infrastructure are security offered?

Finally and most urgently, why are security and safety used to reproduce the division between infrastructural and social aspects of the institution? Is it because governing and controlling material aspects of institutions and social groups in the institution need a different set of skills and tools? Or is it because the desire for infrastructural stability, security of objects and property is always more important than the needs of the communities that are using the institutions or could use them?

In contemporary museum institutions, security measures for the material infrastructures and artworks are often Outsourced to private security businesses. Safeness and the development of safer spaces, in contrast, seems to be Labour that the institution’s internal educational or curatorial staff are responsible for.

What does this say about art institutions when the safeguarding of real estate and art objects requires Outsourced professional labour to “look after” and control the space but offering safeness for individuals and communities is considered the responsibility of the curatorial and/or educational staff?

Yet, maybe both security and safety, despite whose responsibility, have a common aim, one which is not always so apparent. Micheal Kempa, a criminologist specializing in the politics of policing, claims that security, whether it is privatized or offered through public services such as the police or the military, is designed to serve the interests of capital and to reproduce the conditions that keep existing power structures in place. In his essay “Public Policing, Private Security, Pacifying Populations” Kempa writes:

“I challenge the conventional wisdom that the resurgent private security industry amounts to a threat to the public interest that is best dealt with through more active state-led regulation (i.e. ‘democratic anchoring’) and increased public policing to serve collective interest. This is because both public and private policing have common historical origins, and, more deeply, are linked to the same political economy: both sets of modern security agencies work in common towards the pacification of populations in service of growth of markets and thus the interests of capital.”

– Michael Kempa, “Public Policing, Private Security, Pacifying Populations”, in Mark Neocleous and George S. Rigakos (eds.), Anti-Security: A Declaration (Ontario: Red Quill Books, 2011), 86.

In other words, state security and the security industry generally serve the purposes of the ruling capitalist classes. If capitalism is always connected to colonial and class oppression it becomes obvious that security itself is a way to control and persecute marginalized immigrant, subaltern, indigenous, working class and different racialized, gendered and disabled individuals and communities, amongst others, in the interests of capital.

The same book that features this text by Kempa, Anti-Security, opens with the text “Anti-Security; A Declaration” by Editors Mark Neocleous and George S. Rigakos. They write:

“Security is a dangerous illusion. Why ‘Dangerous’? Because it has come to act as a blockage on politics: the more we succumb to the discourse of security, the less we can say about exploitation and alienation; the more we talk about security, the less we talk about the material Foundations of Emancipation; the more we come to share the fetish of security, the more we will become alienated from one another and the more we will become complicit in the exercise of police powers.“

– Mark Neocleous and George S. Rigakos, Anti-Security: A Declaration

(Ontario: Red Quill Books, 2011), 15.

Similarly, safety policies in art institutions can become a dangerous blockage of politics. Safer Spaces and other ethical guidelines and policies can be just a way for Museums, institutions and individuals to tick boxes, in line with neoliberal branding and image control strategies, without any real consideration of individual and situated needs for safety or access within environments and contexts which are often exploitative and alienating for many.

Artist and writer Raju Rage addresses this danger from the point of view of marginalised artists in their text “Access Intimacy and Institutional Ableism” where they outline the problem with “inclusion” as an institutional aim or tactic for people from minority groups:

“In a ‘post-colonial’ and (often problematic) post-racial culture, these institutions have to improve their reputations or lose capital. So, they invite us into this potential violence. They think our very tolerated presence will eradicate the violence, even though we’re in the minority and often don’t have that power. They frame themselves as shrugging off their Colonial ties to history, and ‘including’ those who are excluded, in order to ‘create’ diversity (that already exists) but isn’t embraced, repackaged as new.”

– Raju Rage, “Access Intimacy and Institutional Ableism: Raju Rage on the Problem with‘ Inclusion ’”, Disability Art Online (2020), https://disabilityarts.online/magazine/opinion/access-intimacy-and-institutional-ableism -raju-rage-on-the-problem-with-inclusion / (5.10.2021).

In the worst-case scenario in art museums and institutions safety and safety policies become a way to categorize and control different groups of people and make them behave in a certain way so that they may be included and afforded “security” within the support structures of the institution. In order to act safely and represent individuals and communities, institutions (and their audiences and users) need to know and categorize their identities and qualities. This can easily become a bureaucratic and normalized form of violence that serves capitalist aims to render people into populations that contain categorized groups of simplified identities and qualities.

In Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège De France 1977–1978 Michel Foucault claims that people do not really wish to Belong to the population. Foucault says:

“The people comprise those who conduct themselves in relation to the management of the population, at the level of population, as if they were not part of the population as a collective subject-object, as if they put themselves outside of it, and from the people are those who, Refusing to be the population, Disrupt the system.”

– Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at Collège De France 1977–1978, Graham Burchell (tr.) and Michel Senellart (ed.) (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 43–44.

What are the possibilities for individuals, within the arts and otherwise, to refuse to be Assimilated into the general population? How can institutional and curatorial practice open up space and situations where disrupting the system (which they are inherently part of) is possible?

It is my hope that Rehearsing Hospitalities can nurture practices and ideas that provide a support structure and offer a place of security, safety and hospitality to curatorial, artistic and exhibition practices from diverse yet Interconnecting fields of contemporary art and architecture – while keeping in mind the systemic infrastructures and historical roots of security and safety in order to challenge the violence that security and safeness themselves cause.

— Jussi Koitela

Jussi Koitela is the Head of Programme at Frame Contemporary Art Finland.

This blog is a platform for reflecting work, current issues and discussions in arts by Frame staff members and other contributors. This blog post was published in English.