Photo: Ginevra Formentini

In an article series published on Frame’s blog, invigilators of the Finnish Pavilion in the Venice Biennale write about various topics related to this year’s Biennale. In her text, Jenna Mutanen explores the visitor experience and access architecture of the Pavilion of Finland.

I had a memorable and educational opportunity to work as an invigilator at the 60th Venice Art Biennale for the Finnish Pavilion exhibition The pleasures we choose. During my internship, I profoundly explored the themes of the exhibition and observed how the Finnish Pavilion came to life as visitors moved around and utilized the space. In this blog post, I reflect on my observations regarding the visitors’ bodily interactions with the architectural elements of the exhibition and describe how the improved accessibility measures translated into action. Frame’s Communications Officer Katri Kuisma reflected on her experiences with digital accessibility related to the exhibition in a previous blog post which illuminates this theme further.

The pleasures we choose was curated with a focus on accessibility and inclusiveness, aiming to meet the diverse needs of different people and bodies. Distinctive features of this year’s exhibition are the architectural elements designed by exhibition architect Kaisa Sööt together with the workgroup. These features transformed the pavilion from the inside out in the form of support structures and places for rest. In addition to making the exhibition space physically accessible, it was further enhanced by a tactile map of the exhibition space with a QR code for the publication and an audio description of the exhibition. It was extremely interesting to see how visitors took over the space, utilizing these architectural elements.

I had never before worked in an exhibition where accessibility was considered from so many different perspectives, so this was an extremely good opportunity to educate myself on the topic. In the exhibition publication, access architecture is defined as:

’’The pleasures we choose introduces forms of “access architecture” to support different social, physical and microbial architectures present within the pavilion. – – the “access architecture” that is part of the exhibition at the Pavilion of Finland seeks to intensify and multiply the sensory and physical relays possible between artworks and audiences by offering access tools, spatial guides and places to rest and connect to the space and each other.’’ (Billimore & Koitela 2024: 18.)

Access architecture was a concept I was only vaguely familiar with theoretically, so during my internship, I paid close attention to how visitors interacted with, encountered and utilized the architectural elements to understand it better. As exhibition invigilators interacting with the audience daily, we were able to see how the goal of making exhibition practices and spaces more accessible manifested into reality.

Utilizing the exhibition space

The exhibition architecture created important conversations, reflections and feedback. From my standpoint, the architectural elements were designed in a way that simultaneously created support for those in need, opportunities for rest, and also encouraged visitors to see and rethink how the built environment around us is predominantly designed to serve able-bodied people.

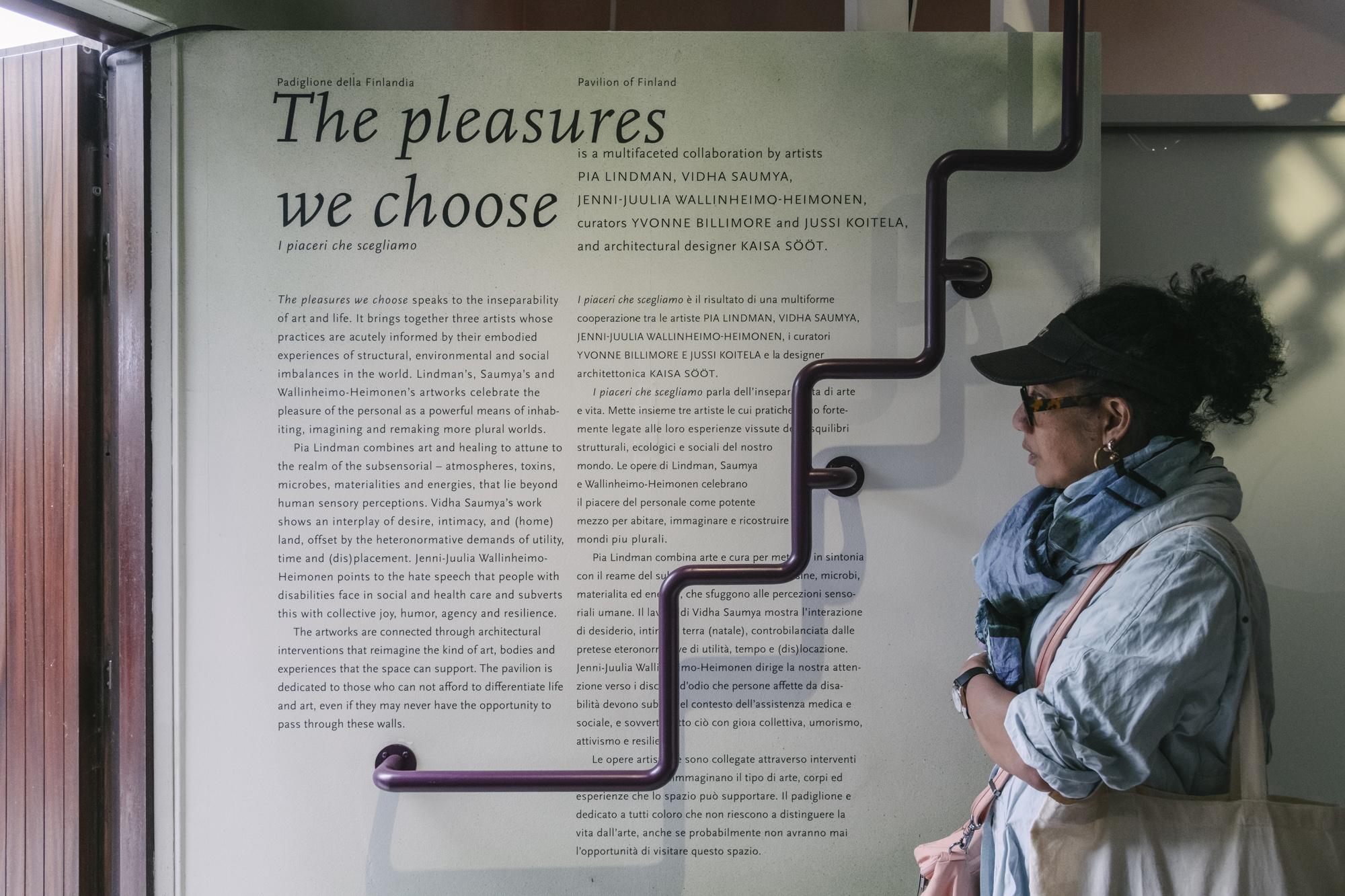

A fine example of this is a railing formed in the shape of stairs placed partially in front of the exhibition text. For the visually impaired, hand railings designed in the shape of stairs are much more accessible and easier to use. At the end of the railing, you can find a recycled wheelchair doing somersaults, an artwork by Jenni-Juulia Wallinheimo-Heimonen. The deliberate placement of this railing partially over the exhibition text elicited interesting reactions and discussions among visitors. Even though this small visual obstacle created some negative reactions, most importantly it created a lot of reflection and raised awareness on accessibility issues.

Another feature that generated similar mixed feelings and feedback was the entrance to the pavilion. The long hand railing extending outside the pavilion was positioned to guide visitors towards the exhibition as well as to provide physical and mental support for those in need. For this year’s Biennale, the ramp at the Finnish Pavilion entrance was elevated and improved. Even though these features were designed to improve accessibility, a large number of visitors rather kneeled and slipped under the hand railing instead of walking around it – creating an unnecessary physical barrier for themselves. Somehow this gesture ironically acted as an introduction to the exhibition in dialogue with the message of access architecture.

While some visitors saw a frustrating obstacle, others saw an opportunity for play, fun, and imagination. Especially families and groups of friends found the seating built outside of the pavilion very welcoming: visitors in need of rest laid down to enjoy the sun, families had picnics with children, and friends sat down to share a laugh. Witnessing how the visitors utilized the space made me understand better what access architecture is all about; creating more opportunities through architectural choices that not only make spaces more accessible for different bodies but also create places to re-imagine them.

Creating opportunities for rest, healing, play and learning

Numerous times we heard visitors sighing with relief as they sat down in our exhibition’s seating areas. I could fully empathize with that sigh of relief, as I was also surprised by how physically and mentally exhausting a day in Giardini can be if one wants to visit all of the pavilions in one day. In such a case, all resting places are welcome — especially those like in the Finnish Pavilion, where the entire exhibition can be enjoyed while sitting down.

The architectural elements and artworks complimented each other seamlessly both thematically and physically in terms of encouraging visitors to stay and enjoy the artworks for a bit longer. Some of the artworks reveal themselves fully once you spend more time with them, like Vidha Saumya’s drawing on a silk fabric which is mechanically moving around at a slow pace. The artwork portrays a never-ending queue of people and criticizes the continuous demands of productivity and utility set by society. The intricate details of this drawing and the slow movement of the fabric that disguises part of the artwork invite the visitor to sit down to rest and analyze it.

The pleasures we choose also offered multi-sensory and even healing experiences near Pia Lindman’s clay installation. The shape of the installation forms a small nook where visitors can sit down to relax, breathe in the purified air, smell the grounding earthy tones of the clay and simultaneously watch Lindman’s meditative digital painting. Visitors who stayed for longer in the exhibition often took their time to pause next to these artworks. Not to mention a certain visitor who found Lindman’s works so calming and relaxing that they fell asleep inside of that little nook for an hour. From our perspective, the healing aspects of these artworks worked wonders – we escaped to that nook for a few minutes when we needed a pick-me-up and it also often cured our colleague’s emerging headaches.

To our positive surprise, especially children seemed to enjoy the exhibition and its architectural features. The fun-colored hand railings and benches outside the pavilion seemed to resemble a playground for the children as they climbed and played around it. In addition, children found other favorite spots in the exhibition — the humoristic video installation by Wallinheimo-Heimonen and the tactile map drew their attention. Children often sat down for several minutes on the floor in front of the video installation mesmerized by it, filling the exhibition space with their giggles. Perhaps the playfulness and humor of the video appealed to younger visitors, but most importantly the screen was placed on the ground where they could enjoy it fully.

The tactile map set up in the exhibition space received a lot of positive attention from visitors along with questions about why similar maps were not available in other pavilions. Again, especially children were particularly curious about the tactile map because it was something they could feel and touch. Whether it’s a visitor touching braille for the first time or parents answering their children’s questions about the tactile map, it created an opportunity for learning something new. We don’t necessarily encounter information provided in braille in many exhibition spaces, so it’s also important to normalize it to improve accessibility measures across the board.

Venice Biennale continues to improve its accessibility

The Venice Biennale describes on its website, that they have taken actions and created initiatives to improve social, physical and mental accessibility by providing clear guides and maps of the exhibition venues, making sure that the pavilions can be entered with a wheelchair and granting free access for people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to experience the biennale. In terms of showcasing the stories and artworks made by marginalized people, this 60th Biennale with the theme Foreigners Everywhere also created a chance to highlight many marginalized voices through national pavilions and collateral events.

While new steps are taken at every biennale to improve accessibility, the work is not yet complete. Enabling and investing in accessibility is also a message about the kinds of audiences that are welcomed. Based on the feedback we got from the visitors, many were positively impressed by how accessibility was improved in our exhibition. Some visitors for example photographed the tactile map as an inspiration for their work with exhibition practices. I believe that an art event as prestigious and substantial as the biennale, may and will inspire and show an example for others so that the art field itself can continue the progress of accessibility.

As someone studying cultural heritage, I believe and hope that the understanding of accessibility measures I gained through the internship will stay with me in the future so that through my choices and contributions, I can continue to expand the accessibility of exhibition spaces and cultural services in more diverse and opportunity-creating ways.

– Jenna Mutanen

Student; Exhibition invigilator, Pavilion of Finland

This blog is a platform for reflecting work, current issues and discussions in arts by Frame staff members and other contributors. This blogpost is publisheed in English.