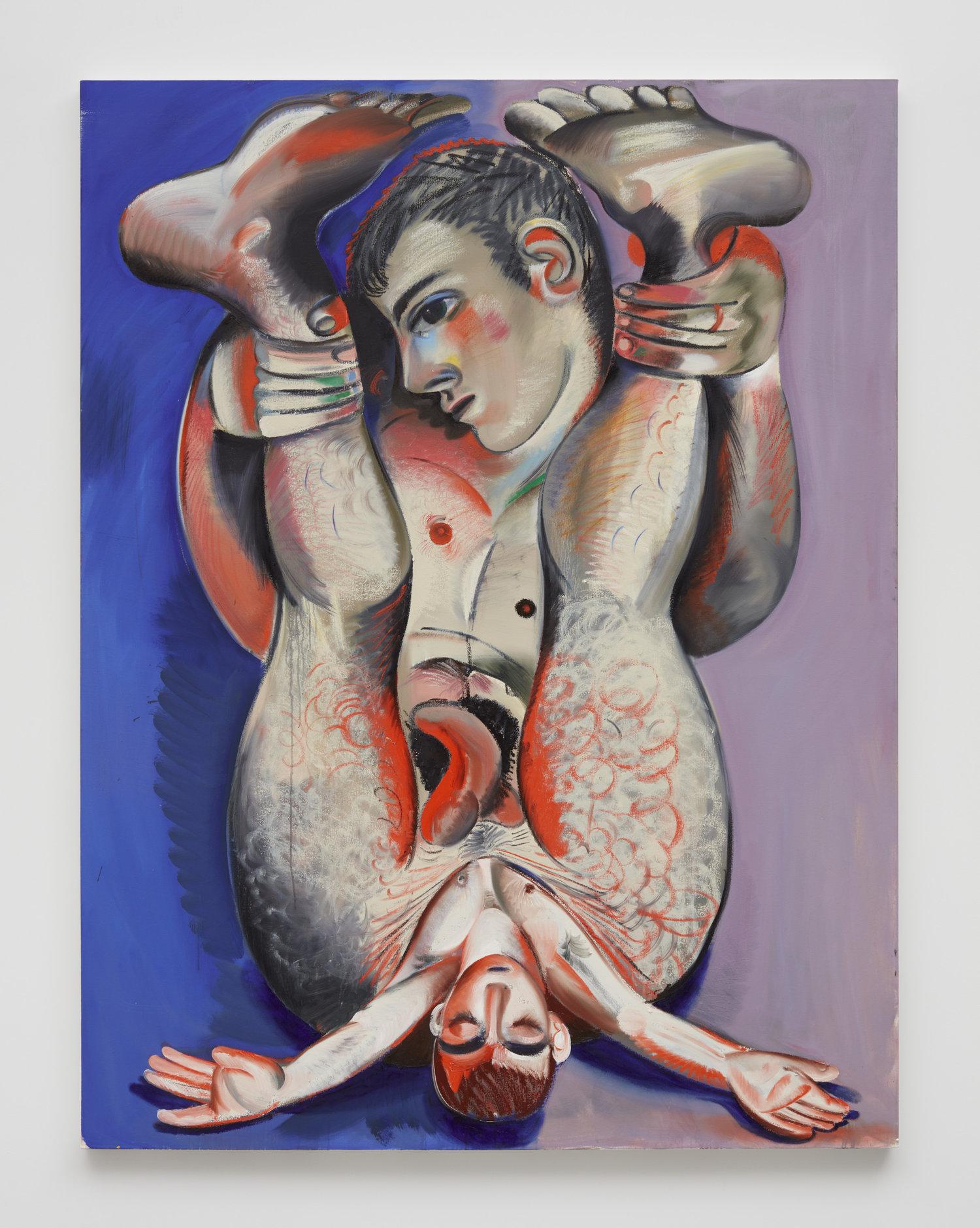

Louis Fratino, An Argument, 178 x 165 cm, oil on canvas, 2021. Foto: Matteo de Mayda. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.

In an article series published on Frame’s blog, invigilators of the Finnish Pavilion in the Venice Biennale write about various topics related to this year’s Biennale. Rebekka Yallop writes about Louis Fratino’s paintings exhibited in the Venice Biennale main exhibition.

The room throbs in a pale yolk glow. Honey up the walls. A warmth fades at the sides, obscured by a thick oil-black window frame. Two men lie nude, separated across a room where one stretches out in bed, the other cramped on a sofa. Eyes closed they mirror each other, doubled, not quite at ease in their half-slumber.

An empty bowl, a spoon, a glass, a fork in the sink, trainers, a broom, a knife. Scissors on the counter. Kettle on the stove. An orb-like lamp casts its golden illuminations.

*

Louis Fratino’s paintings in Giardini’s main pavilion show domestic interiors, heaving nightlife, surreal twisted bodies, terrace bars and kitchen tables. They remind me of Hockney and Cocteau as well as Nicole Eisenmann’s vast paintings of surreal scenes, various hued figures and queer intimacy. Eisenmann’s Morning Studio is almost a reverse of Fratino’s The Argument, depicting a couple curled up together on a futon, projector set up behind them. In the large-scale, bold, camp and absurd paintings, queer lives take on multiple forms. Figures together and alone, taking up space. They playfully skew ideas of what images are worthy of capturing, which bodies, which stories. The ordinary has the potential to become surreal – maybe it always was – where in an immaculate conception mixed with body horror the artist gives birth to himself.

*

The piano stool is half-pulled out, the chairs around the kitchen table askew. Things are off-kilter. Other rooms are hidden in shadows. The darkness seeps across, perhaps out of the frame’s matte cross, while the outside world is blocked by reflection. Nothing to see out there but the light shining back.

Out of the muddied yellow hues a figure reclines, arm stretched back, skin glowing in mustard, beside objects placed on the windowsill. Nick-nacks, shells, souvenirs perhaps. His limbs are folded strangely, leg bent back. Shadows pool in the crevices of his body as he faces away from the room, towards us.

*

Bhupen Khakhar’s Fishermen in Goa (1985) hangs beside Fratino’s The Argument. It’s a shame that there aren’t more of his works here. Both artists lavish over the details, there are things to notice, that demand attention. Three men sit in the foreground, trousers off, one completely nude. The sun makes their bodies glow – a shoulder blade, an ear, knees, a chin – they are illuminated by it, or perhaps it is coming from them, shining out from their skin. They behold their catch, carefully arranged while a hand reaches out, makes contact, but eyes remain averted. They look out, but not at each other, not yet. There’s a private stillness as the men sit apart from the distant figures on boats. I wonder if a voice is carried, or it’s just the sound of the waves tumbling up the shore, glimmering in blue before falling onto the sharp rock’s edge.

Louis Fratino, I keep my treasure in my ass, 2019, oil on canvas, 86 x 65″. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co

I was thinking about what paintings and images I’m drawn to. Brian Dillon writes about the idea of ‘affinity’ – the attraction or fascination we feel towards a fragment, image, sentence. It can also be ‘moods or atmospheres inside of them’ – something intangible that draws us in. Perhaps this is what I was drawn to – a mood of the painting, a glow that remains, but it can’t always be traced back to why. There is something of the beyond-knowing about it – why certain images stay, encourage us to stop, even for a second longer, or think about on the way home, on the vaporetto, gliding across Venice, before sleep. A photograph discarded on the street, an image in a textbook, a drawing taped above a desk – Dillon realises many images he is drawn to are ‘in their content or form some act of blurring and becoming’. Perhaps I’m drawn to something, a sense of isolation, an unanswered question, a look. Sometimes it’s the arrangement of specific colours, an atmosphere. It feels trite to overanalyse it, but I want to know.

*

Returning to The Argument, I notice the scale of it, it seems bigger, growing the more I look. The figure on the sofa has something round and dark by his legs. Maybe a cat, curled up. I peer into it, close up, while someone behind me takes a picture, steps back, circles round. The angles make it feel like I’m looking both down and across, both outside the painting but also very close. The fact that there’s a window separating the figures… the sleeping man could look over, but his eyes are firmly shut. The light’s been left on.

*

There’s a magnetic draw to certain paintings in the Biennale that I can’t quite explain, often catching a glimpse of something I haven’t yet noticed, pulled towards colours and details. In a curious text, What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet, Jean Genet writes about looking. The text begins with an experience on a train where he looks at a stranger and feels he is ‘flowing out of my body, through the eyes, into his at the same time as he was flowing into mine’. This sort of flowing exists too in seeing paintings, where he writes about Rembrandt’s works, the fleshy nature of them where ‘the bodies are performing their functions: they digest, they are warm, they are heavy, they smell …’. It feels like Genet is trying to work out why we forge affinities, making revelatory connections with a glance. ‘Why do I feel like that? What are those paintings that I can’t shake off?’.

*

My Meal, Louis Fratino, 2019, Oil on canvas, 43 x 47 inches (109.2 x 119.4 cm). Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co

One of Fratino’s paintings is curiously separate from the rest – a portrait called Alessandro in a Seersucker Shirt (2024). I wonder why. Nearby there are works by Dean Sameshima, photographs of lone figures in an adult cinema. Back of heads, white screen. Empty cinema seats, a bottle, a glow. The series is called being alone (2022). In the same corridor are photos by Miguel Angel Rojas, also of obscured faces, blurred bodies, indistinguishable, framed by the hole in a bathroom wall (El Emperador 1973-1980). A painting by Sameshima nearby reads ‘Anonymous Homosexual’. It’s a curious arrangement, perhaps knowingly placed by the bathroom, where they’re in stark contrast to the moments of queer intimacy and tactile bodies of Fratino and Khakhar’s paintings. Here there are faceless people, anonymous shoulders, backs of heads. They reflect aspects of gay culture that are slowly disappearing, cruising spaces and cinemas that were vital, but something about the images, taken covertly, feels unsettling.

By looking we could also mean searching, staring, gawping, leering, admiring, spectating, observing – I’m not sure where the line is between observer and voyeur. I’ve been looking and looking. There’s something about paintings, in contrast to photographs, that emphasises a common experience rather than freezing in time a real person in a private moment. Objects take on a life of their own, repeat, reappear, with references to queer culture existing alongside nods to art history. The washing up is still stacked in the sink, where a face is reflected in the tap. Tins of tomatoes. A receipt. Eggs. Eggs are all over the place. Boiled eggs. A chair casts a shadow onto the wall while a sketch almost falls off the side of the table. A still life with flowers and coffee also includes nude photographs and a copy of ‘Towards a Gay Communism’. Terrace bars with wine, sucking spaghetti, humid nights, voices out of the dark. We’re invited in, observing mess, clutter, sketchbooks, the morning light spilling into a bedroom.

I return to The Argument again, perhaps drawn to it because queer lives are simultaneously joyous and messy, where isolation and intimacy aren’t separate but entwined. A tiff, a quarrel, an argument – it’s specific yet also, I feel I’ve been there. It’s a mood, the light is still on, eyes bleary. Everyday moments are the point, with nightlife, drinks out, breakfast, dreamscapes all flowing into each other. The window obstructs our view from one man, but not the other. He could look out, through the window, onto the kitchen where the other man lies. He doesn’t, yet. The lamp flickers, slowly breathing, alone but not quite, since we look at them. I’m not sure what will happen next.

– Rebekka Yallop

Student; Exhibition invigilator, Pavilion of Finland

This blog is a platform for reflecting work, current issues and discussions in arts by Frame staff members and other contributors. This blog post is published in English.

References:

Brian Dillon, Affinities (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023)

Jean Genet, What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet, trans. Randolph Hough (Hanuman Books, 1988).

1. Fishermen in Goa, Bhupen Khakhar (1985) https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/bhupen-khakhar

2. Brian Dillon, Affinities (London, Fizcarraldo Editions, 2023), 19.

3. Dillon, Affinities, 22.

4. Jean Genet, What Remains, 13

5. Jean Genet, What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down the Toilet, trans. Randolph Hough (Hanuman Books, 1988), 36.

6. Jean Genet, What Remains, 43.

7. Dean Sameshima, being alone (2022). https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/dean-sameshima

8. Miguel Ángel Rojas, El Emperador 1973-1980. https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2024/nucleo-contemporaneo/miguel-%C3%A1ngel-rojas